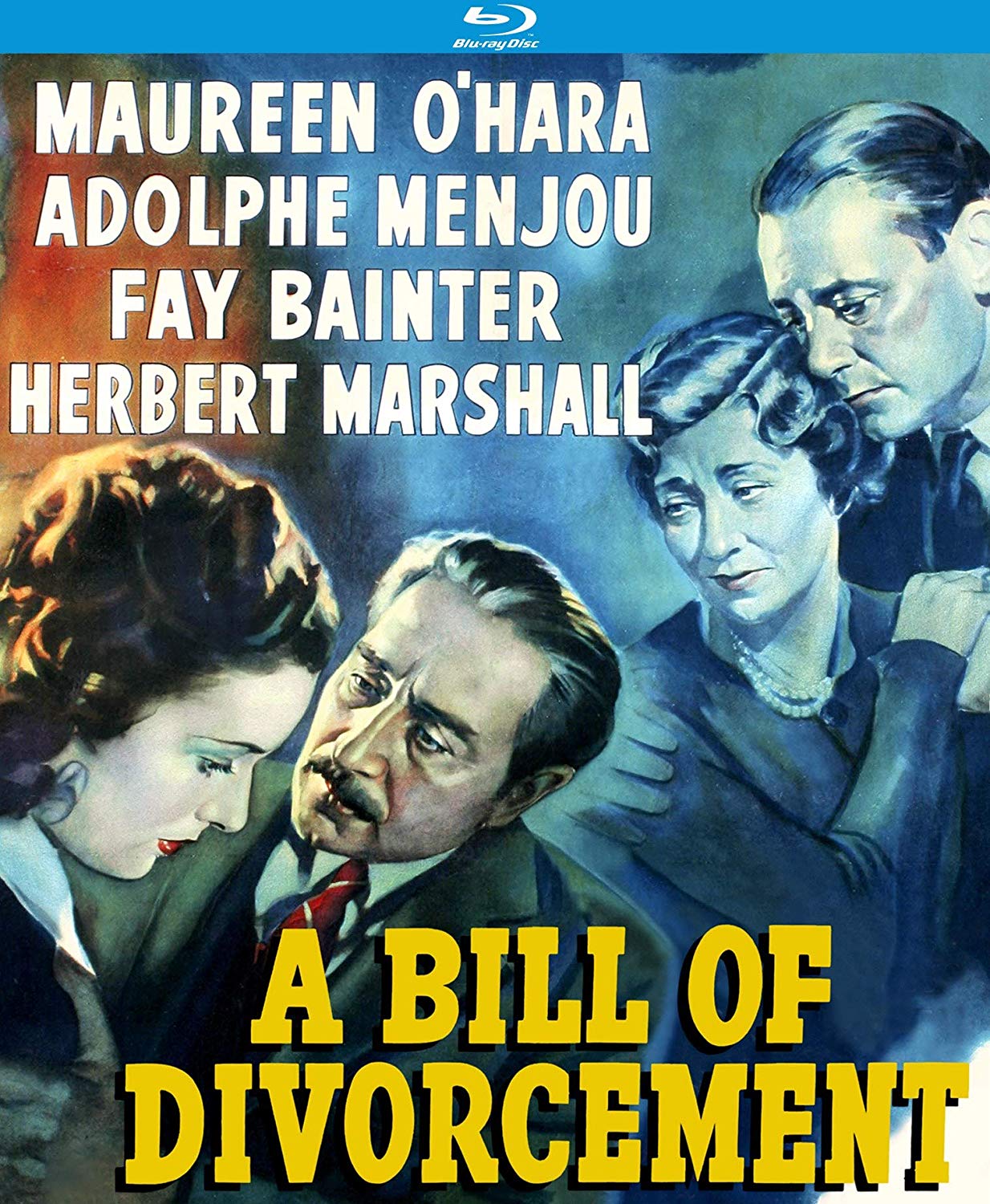

Though it lacks the raw electricity of the 1932 Katharine Hepburn/John Barrymore version, the more sedate 1940 remake of A Bill of Divorcement employs a fine cast to tell a delicate if dated story of domestic strife and mental illness.

A Bill of Divorcement (1940)

Theatrical Release Date: May 31, 1940

Blu-ray Release Date: February 26, 2019

Directed by: John Farrow

Starring: Maureen O’Hara, Adolphe Menjou, Fay Bainter, Herbert Marshall

Blu-ray Special Features: Assorted Kino Lorber Studio Classics trailers

If you’re a Golden Age movie fan and someone mentions A Bill of Divorcement, you probably think to yourself, “Oh, of course! Katharine Hepburn’s film debut.” But if you’re an over-the-top, utterly obsessed classics addict like I am, you follow up instead with, “Do you mean the 1932 Hepburn version or the 1940 remake with Maureen O’Hara?” “Wait a second…” the reply might be. “There was a remake of A Bill of Divorcement? With Maureen O’Hara? Never heard of it.”

The reason for that is simple. Despite a stellar cast, fine acting, good direction, and attractive production values, the 1940 adaptation remains largely unknown because it arrived on the cinematic scene a mere eight years after the George Cukor-directed original. That’s a pretty short time span even by Hollywood remake standards. Not surprisingly, at the time of its release, audiences weren’t yet ready for a Divorcement redux, especially since the memory of Hepburn’s dazzling debut, which instantly launched her into the upper echelon of Hollywood’s elite, remained so fresh. RKO hoped the slightly revamped material would similarly catapult the 19-year-old O’Hara, who made quite a splash the previous year as the gypsy Esmeralda in The Hunchback of Norte Dame, to A-list stardom.

Lightning, however, didn’t strike twice. Though the red-haired, fresh-faced Irish actress gives a capable performance and is ably supported by such esteemed veterans as Adolphe Menjou, Fay Bainter, Herbert Marshall, and Dame May Whitty, she’s not magnetic, different, or even talented enough to commandeer the screen the way Hepburn did and still does. (I watched Hepburn’s version again in preparation for this review and the electricity she generates remains palpable.) As a result, this A Bill of Divorcement brings nothing new to the table. On the plus side, it still manages to tell a dated, somewhat trite story with warmth, sensitivity, and nuance.

From its title, you might expect A Bill of Divorcement to chronicle a failing marriage, but it’s really a story about the ravages of mental illness. Beautiful, headstrong Sydney Fairfield (O’Hara) lives in a lavish English estate with her impeccably mannered mother Meg (Bainter) and crotchety Aunt Hester (Whitty). She’s deliriously in love with the handsome John Storm (Patric Knowles) and looks forward to marrying him and bearing several children. Meg is also in love. Her beau is the dapper, refined Gray Meredith (Marshall), and he offers her the affection and adoration her ex-husband, Hilary (Menjou), could never sufficiently express.

Why? Most notably because Hilary has been confined to a mental institution for two decades due to the shell shock he experienced during World War I. He has never met his daughter, and his inability to relate to his wife has led her to divorce him. On the eve of Meg’s marriage to Gray, however, Hilary escapes from the hospital after miraculously regaining his sanity. (Whether his recovery will be permanent, no one knows.) He returns home hoping to resume the life he once had, but doesn’t receive the rapturous reception he anticipates. Meg pities him, but no longer loves him, and when Sydney discovers an age-old, shameful family secret, she’s faced with an agonizing choice that will forever change her life.

Prior to A Bill of Divorcement, mental illness was largely a taboo topic in Hollywood, and its rather simplistic, almost Victorian treatment here doesn’t do much to widen awareness or maturely address a prevalent and complex disease. The film’s strength lies in its depiction of dysfunctional family dynamics, even if the decisions the heroine ultimately makes seem more than a little impulsive, misguided, and dramatically driven.

Despite all that, I’m surprised I liked this version of A Bill of Divorcement as much as I did. Before I sat down to watch it, I mistakenly equated its relative anonymity with mediocrity, and that was a mistake. Director John Farrow (Mia’s dad) treats the time-worn tale with respect and wisely tamps down the histrionics that plagued the previous version. (Barrymore’s broad portrayal in the 1932 film seems rather cartoonish today.) These performances, however, subtly convey the conflicting emotions that rip apart the characters without pushing the boundaries of credulity. Bainter, whose work enhanced countless films of the era, is especially effective as the conflicted wife whose warped sense of duty outweighs the love she feels for her devoted fiancé. Menjou brings just the right amount of confusion, paranoia, and angst to his mentally disturbed character, while Marshall excels as Bainter’s patient, understanding lover, and the indomitable Dame May Whitty adds some necessary spice as the cranky family aunt.

Let’s face it, O’Hara is no Hepburn, especially at age 19. She lacks Hepburn’s fiery magnetism, and it’s unrealistic to expect the young actress to eclipse her legendary counterpart in the role that made her a star. Wisely, O’Hara doesn’t try to compete. Earnestness and quiet conviction help her file a winning performance, especially during her scenes with Knowles, where she truly proves her dramatic mettle. Screenwriter Dalton Trumbo nicely beefs up their on-screen romance, lending the film even more heartache and additional resonance. Though Trumbo otherwise sticks pretty closely to the 1932 script, his contributions bolster the movie’s impact.

Remakes rarely outshine a film’s original version and this one doesn’t, but it’s always fascinating to compare and contrast them. The 1940 version of A Bill of Divorcement may not be memorable, but it holds up better than most remakes and stands on its own as an involving and affecting drama. If you only see this version and never lay eyes on the 1932 Hepburn/Barrymore film, you really won’t be missing that much.

The Blu-ray

The 1940 version of A Bill of Divorcement comes to Blu-ray presented in its original aspect ratio of 1.37:1. The 1080p/AVC MPEG-4 transfer has been struck from a “brand new 2K master” that injects newfound vitality into the almost 80–year-old film. Well-balanced contrast and surprisingly good clarity distinguish the rendering, which features light grain, rich black levels, excellent gray scale, with only a smattering of nicks and blotches. (There’s a missing frame at one point early on, but no other print anomalies.) Background details show up nicely, shadow delineation is fine, and sharp close-ups highlight the young O’Hara’s fresh-faced beauty.

A Bill of Divorcement is a quiet film, but thankfully the DTS-HD Master Audio mono track has been nicely restored. Any age-related hiss, pops, or crackle have been erased, so the frequent silences are pure and nothing distracts from the softly spoken dialogue. The musical score by Roy Webb is used sparingly, but sounds full-bodied. The only disc extras are a few trailers for other Kino Lorber Studio Classics releases, but not one for A Bill of Divorcement.

Eugene Kozma

I LIKE THE 1940 VERSION FAR FAR BETTER THAN THE 1932 VERSION!

EM

Regarding remake turnaround time: Only five years separated The Maltese Falcon (1931) and Satan Met a Lady (1936), and just another five years passed before the most famous version of The Maltese Falcon hit the silver screen in ʼ41. (!)