[Editor’s Note: This week, our friend and frequent Roundtable contributor Adam Tyner from DVDTalk has agreed to help us out with a review of the latest cinematic tome from Titan Books, publishers of the impressive ‘Alien Vault‘. Give Adam a warm welcome as he cracks open ‘The Hammer Vault’. -JZ]

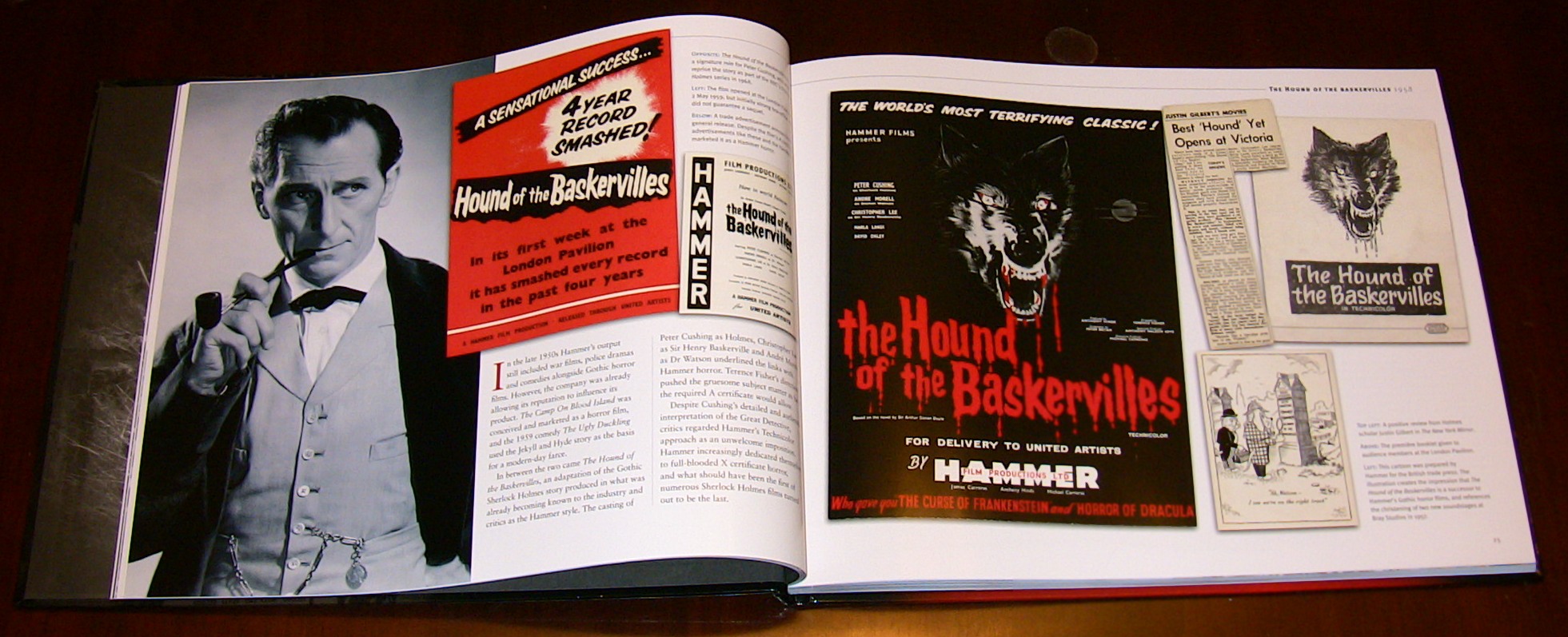

Hammer Films has produced more than 150 movies throughout its storied history, and has seemingly spawned just as many retrospectives. As written and compiled by film historian Marcus Hearn, ‘The Hammer Vault’ sets itself apart from the scores of other books honoring the Gothic horror of the legendary British studio. Hearn charts the rise and fall of Hammer Films visually, scouring through Hammer’s archives and unearthing everything from preproduction artwork to Christopher Lee’s annotated script pages.

Having already overseen several books about the studio, Hearn strikes an intriguing balance with ‘The Hammer Vault’. On the one hand, it’s a coffee table book that’s a blast to simply thumb through. It’s intensely visually oriented and limits each film to no more than a two-page spread. At the same time, there’s a story unfolding here. Though the write-ups for each film are brief, the personalities behind Hammer Films – on both sides of the camera – quickly start to take shape. Hearn shies away from rote plot summaries, instead detailing what makes these movies significant or unique in Hammer’s sprawling filmography.

‘The Hammer Vault’ readily acknowledges the lesser films from a studio that was shackled by its enormous success in a very specific brand of horror. The book often details Hammer’s failures in the words of its own filmmakers. Hearn’s writing is concise and compelling. There’s enough context for casual Hammer fans to readily follow along, even if they’re completely unfamiliar with some of the obscurities that ‘The Hammer Vault’ covers. It’s also written in a way that shouldn’t come across as more of the same for seasoned Hammer scholars.

‘The Hammer Vault’ readily acknowledges the lesser films from a studio that was shackled by its enormous success in a very specific brand of horror. The book often details Hammer’s failures in the words of its own filmmakers. Hearn’s writing is concise and compelling. There’s enough context for casual Hammer fans to readily follow along, even if they’re completely unfamiliar with some of the obscurities that ‘The Hammer Vault’ covers. It’s also written in a way that shouldn’t come across as more of the same for seasoned Hammer scholars.

‘The Hammer Vault’ doesn’t let itself be shackled by the Gothic horror that largely defined the studio. It also explores the likes of the heist thriller ‘Cash on Demand’ and the space-Western ‘Moon Zero Two’ with every bit as much care and attention as ‘The Curse of Frankenstein’. There’s also a section devoted to such unproduced Hammer films as ‘Zeppelin vs. Pterodactyl’ and a Richard Matheson-scripted adaptation of ‘I Am Legend’.

As much as I appreciate Hearn’s writing, the real selling point for ‘The Hammer Vault’ is what he has uncovered in the studio’s archives. The book showcases a tremendous variety of material: lobby cards, production and promotional stills, press and publicity books, script pages, press clippings, novelizations and poster art from around the world, poster art painted when many of these movies were nothing more than a title, telegrams, editorial cartoons, call sheets, promotional gimmicks, lists of cuts demanded by the American distributors, and even photos of a few of the props that have somehow survived over these many decades. Among the many highlights are script pages from ‘Taste the Blood of Dracula’ that had been annotated by a thoroughly frustrated Christopher Lee, a shot of Clytie Jessop leisurely reading ‘The Long Goodbye’ with a stake jutting out of her blood-soaked gown, Sammy Davis, Jr. palling around with Lee on the set of ‘The Pirates of Blood River’, conceptual wardrobe art painted by Peter Cushing himself, and a mummy triumphantly raising a glass of milk. All of this material is reproduced remarkably well, and the letters, press clippings, and screenplay excerpts are printed so clearly that you can (and should!) read them. Even though these films generally only get two pages each to play with, designer Peri Godbold skillfully fits a lot into that space.

‘The Hammer Vault’ is a striking book, beginning with the hardcover’s appropriately wide and cinematic dimensions. The metallic, blood red text on the cover and the painted image of Dracula preparing to sink his fangs into some impossibly gorgeous victim are immediately arresting, and the pages within are printed on glossy, heavy stock. The dozens upon dozens of films featured throughout ‘The Hammer Vault’ are presented chronologically, furthering the progression of the story that Hearn tells. This also means that the further readers delve into the book, the more lurid and visceral the artwork becomes, reflecting Hammer’s heightened fascination with blood and breasts in its later years.

‘The Hammer Vault’ isn’t meant to be an exhaustive study into the studio. The book is uninterested in the films that preceded ‘The Quatermass Experiment’ and glosses over many of Hammer’s comedies, adventure films and even the occasional horror movie. Those seeking a more comprehensive list of films or detailed plot summaries may want to supplement this book with Hearn’s ‘The Hammer Story’. One advantage ‘The Hammer Vault’ has over that earlier release is that it’s able to document the studio’s revival in the past few years, including ‘Let Me In‘ and the criminally underseen ‘Wake Wood’.

As high as my expectations were going in,’ The Hammer Vault’ easily trumped them. As a visual document of the studio that defined horror cinema throughout the 1950s and ’60s, it’s remarkable. I’m pleased that the book is every bit as compelling to read as it is to just look at. Its design and craftsmanship are also first-rate, especially considering how reasonable the asking price is. (As I write this, at least, ‘The Hammer Vault’ costs less on Amazon than the Blu-ray release of Hammer’s ‘Vampire Circus’.) The material is accessible enough for casual fans only familiar with Hammer’s best-known movies, and it’s compelling and diverse enough to intrigue longtime horror enthusiasts as well. Very highly recommended.