As part of this year’s Fidelity Forum conference, Dolby Labs invited a group of home theater writers to the company’s headquarters in San Francisco for a tour of the facility and a look at some of its latest and greatest tech. The highlights of this two-day event were demonstrations of two new products. As I described in yesterday’s post, I wasn’t entirely sold on the need for 96k upsampling. However, the unveiling of the new Dolby Atmos theatrical sound format is considerably more exciting and easier to appreciate.

Ever since the resurgence of 3D video, both in theaters and at home, industry professionals have been actively discussing ways in which to upgrade and enhance movie soundtracks to bring a similar “3D” experience to audio. But wait, isn’t surround sound already “3D” in a sense? That’s a fair question. After all, sounds come at you from all around the listening space, both in front of and behind your seating position. While that’s all well and good, the modern standard for movie soundtracks is currently limited to only 5.1 or (more recently) 7.1 discrete channels of sound. That may seem like plenty enough for most viewers, but the formats have their drawbacks and limitations.

For example, the space between channels often leads to a “ping-pong” effect as sounds bounce from speaker to speaker. Take the case of a movie soundtrack with an airplane sound that’s supposed to travel from the front of the room to the back. In a 5.1 or even 7.1 configuration, the sound will jump from in front of a viewer to behind, with a gap in the middle. The larger the listening space, the more unnatural this sounds. Sure, the mixer will attempt to compensate for this by fading the sound out of the front channels and fading it into the rear channels, as well as applying phase effects to mask the transition, but there’s still a hole in the middle of soundstage. Professional theaters try to fill this hole with speaker arrays along the side walls, but all of the speakers on one wall are tied to a single surround channel, which means that what you hear directly to the side is exactly the same as what you hear behind you at the same time. The pan from one end to the other will be choppy, rather than smooth. There’s also a huge void overhead, which is logically where the sounds of an airplane should come from.

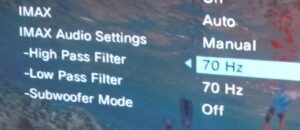

So, what can be done about this? The natural instinct is to add more speakers and more channels. In theaters, IMAX and some other premium venues implement proprietary sound formats and speaker configurations. To properly benefit from these, a movie will have to be mixed for the specific formats. (Any movie that plays in an IMAX theater must have a dedicated IMAX sound mix). This of course puts an extra burden on the mixer to prepare multiple soundtracks for each movie, some of which will never be used again after the theatrical run.

In the home theater environment, many A/V receivers now incorporate Dolby ProLogic IIz, DTS Neo:X or Audyssey DSX processing that will upmix a standard 5.1 or 7.1 soundtrack to as many as 11.1 channels (which would entail a 5.1 base with two surround back speakers, two height speakers above the front soundstage, and two width speakers on the sides of the room). This processing is done in real time and, aside from some phase and steering cues that can be embedded in the tracks, takes a degree of control over the soundtrack away from the original creators and sound mixers. This isn’t ideal either.

When trying to figure out just how many channels should be implemented as a new surround sound standard (NHK in Japan recommends 22.2 channels as the new Ultra High Definition Television standard), audio specialists across the industry (not just at Dolby) decided to throw out the rule book and devise a whole new process known as object-based sound mixing. This represents an entirely new paradigm in sound design.

How so? In a traditional movie soundtrack, sounds are tied to specific channels. If you want to pan a sound from left to right, you have to lower the volume and ultimately remove it from the left channel, raise and then lower it in the center channel, and finally raise it in the right. The more channels you work with, the more difficult this becomes. This process also commonly results in situations where particular sounds get isolated to a specific channel when they should more naturally radiate out further into the room.

Object-based sound design, on the other hand, models the entire listening area as a three dimensional space. Sounds are tied as metadata to specific objects within that space. As the object moves, the sound moves with it towards whatever the nearest speaker happens to be. In this way, a single sound mix can accommodate as many channels as are in the room, fully scalable from a simple stereo pair up to 64 discrete speakers or possibly more – in the front, back, along the sides, and even up above. During installation, the processor will determine the number and position of speakers, and perform the necessary calculations in real time to place sounds where the original mixer wants them to be.

Perhaps the easiest way to think of this is the same way that the visuals in CG animated movies or videogames are similarly rendered as objects in a three-dimensional space, through which a virtual camera can maneuver to pick and choose camera angles. In fact, the sound design for videogames has employed a version of object-based rendering for years. (Notice the way that the sounds of other characters speaking or explosions near you will swing from channel to channel as you change your own character’s direction and point-of-view.) Yet this has not been used for movies until now.

As I said, more companies than just Dolby are working on this. However, Dolby is first to market with a new product called Atmos that will debut in about 15 specially-installed theaters with the release of Pixar’s ‘Brave’ in June. According to company reps, the average cost for a theater to upgrade to Atmos will be about $25k to $30k, depending on what equipment is currently installed. This entails a new sound processor, new speaker amps, and potentially additional speakers. While Atmos is designed to configure to whatever speakers are already in place, it requires discrete amplification to each (as opposed to the array configurations that most theaters currently use). For the best experience, ceiling-mounted speakers above the audience are also recommended. Most of the initial theaters to receive Atmos will be upgraded from the AMC chain’s “ETX” auditoriums, which already have a speaker layout that’s well suited to Atmos integration.

How does it sound? Dolby gave us a demo in the facility’s main screening room, which we were told was outfitted with a 26.3 sound system. Six of those channels were overhead. (In larger auditoriums, Atmos can go up to 64 discrete channels.) We listened to a variety of content that included audio clips of a rainstorm, a musician walking all around the room, and dialogue from ‘The Dark Knight’. We then watched Dolby’s new Atmos trailer (which has sound design from the mixers of the ‘Transformers’ movies, and sounds very similar to the opening credits of the last one of those), the climax of ‘Rise of the Planet of the Apes’, and a lengthy scene from a very famous and popular animated movie that I’m not allowed to disclose due to some ridiculous licensing restrictions that the Dolby reps apologized profusely for.

Needless to say, they all sounded great. Specifically, the pinpoint directionality and seamless panning of sounds as they dashed around the room (including overhead) was very impressive. This created an incredibly precise sense of localization and immersiveness. Essentially, Atmos conveys the feeling that you’re standing (or sitting) right in the middle of the movie’s space. This also allows for heightened clarity of individual sounds. For example, one of the clips came from a scene in a restaurant where two different sets of background characters were having conversations audible in the surround channels. In standard 5.1, the dialogue muddled together and was largely overwhelmed by the foreground action and other ambient sounds in the location. But in Atmos, both conversations were clear and distinct. That’s a benefit that could apply to any sort of film, whether an intimate character drama or a bombastic action blockbuster.

For the time being, Atmos is only planned as a premium theatrical experience, though I expect that Dolby surely has long-term plans for a home version that could be integrated into A/V receivers. Doing so may require a new compression codec and a revision to the Blu-ray spec, though.

One thing that all of the Dolby reps were insistent upon was that Atmos (or object-based audio in general) is a “ground up” approach to sound design, and is not intended to be used to upmix existing movie soundtracks into multi-channel. All of the clips we listened to were remixed specifically for Atmos from the original sound elements. However, once an Atmos mix is created, the processor can easily downmix and render out any standard stereo, 5.1 or 7.1 format as desired. This sort of elasticity makes it both backwards-compatible with legacy equipment and future-proof for sound systems with as many speakers as someone wants to install.

Whether it be Dolby Atmos or a competitor product from another company (we’ll get to that later in the week), object-based sound design represents a revolution in the way that movie soundtracks are created. No longer will filmmakers need to create dedicated stereo, 5.1, 7.1, 9.1, 11.1, or IMAX, etc. sound mixes. There will only be one fluid soundtrack, adaptable to any playback configuration needed now or in the future. This will have major ramifications for the filmmaking industry.

Barsoom Bob

Okay, I like the sound of that. LOL

I’m glad you did get so specific about the mixing/panning techniques, because I did take exception in Michael’s write up that you could not generate a 360 degree sound field with just four speakers. Pink Floyd always performed in quad sound, I attended concerts at the Filmore East and Carnegie Hall where they would place and wire speaker stacks at the rear of the auditoriums and balconies. During “Cymbeline” they would turn the lights almost all the way off and had sound tapes of a guy walking and running all around the audience slamming doors in various locations. It was pretty darn seamless, but these were intimate venue shows not stadiums. They even had a real time quad panning device, think Atari joystick, and during this float-y break in Set the Controls for the Heart of the Sun, Rick Wright, the organist could manipulate his ethereal oragan solo around and across the audience as he was playing it. They called this device The Azimuth Coordinator.

Michael S. Palmer

Hi Bob. I don’t believe I said “you could not generate a 360 degree sound field with just four speakers.” I’m not sure where you got that. Perhaps it was when I described what 5.1 panning was like in a professional theater with 20 wall speakers and how the levels didn’t line up as discretely as the Atmos mix?

Personally, I think in the home environment, whether it be quad, 5.1, or 7.1, it’s less of an issue because we tend to have the exact same number of speakers as discrete sound channels. This makes the experience more convincing and accurate, I think. In most cinemas, individual channels play over multiple speakers, so the pans are less accurate in 5.1 than in Atmos, where objects could be placed in individual locations rather than “sections” of a wall.

But again, no where did I say 360 degree panning could not be convincingly generated with just four speakers. Heck, I didn’t even consider anything less that five 🙂

Barsoom Bob

Michael, It wasn’t you. It was in the Atmos demo clip. The Dolby guy was saying something to that effect, that it was either or, front or back, with no placement in between. Sorry for the confusion. I wasn’t speaking in reference to any home theater set up, his assertion just struck me the wrong way as I know it is possible to pan something 360 degrees with just four speakers. Josh filled in the missing details about the drop out if the spatial distance is too great.

JM

I don’t know if I can fit 29 speakers in my den, but I’m willing to try.

EM

This is indeed more interesting and exciting news, at least for the long term. On the other hand, I’m disappointed it’s taken so long. Not that I’m all that knowledgeable about the engineering involved, but it seems like something like this should have been built into Blu-ray already. Maybe it would have been if there hadn’t been a brewing format war forcing looming deadlines.

Josh Zyber

AuthorThis really has very little to do with Blu-ray. It’s a sea-change in the way that movie audio is produced. I’m not sure how much of this could have been forseen at the time the Blu-ray spec was established. That’s sort of like saying that 5.1 surround should have been built into the VHS spec. Movies just weren’t produced that way at the time.

EM

I know it has, present tense, very little to do with Blu-ray; that’s what I’m lamenting. As you say in the article, videogames for the home market have already been produced using object-based sound design for years. Surely there have been audio professionals in the film, television, and home-video industries who have been thinking about the general technique for quite some time. I do disagree on a personal level with your claim, “The natural instinct is to add more speakers and more channels”: while I had no name for it, object-based sound design is what I have long thought was a more logical (if possibly pie-in-the-sky) approach to multichannel audio. I understand that, had OBSD been included in the Blu-ray specs a few years back, there would have been little or no content ready to take advantage of it; but what I am saying is that OBSD is just the sort of technology that I would have hoped the next-generation HD-video format should have been forward-looking enough to readily accommodate. And yes, it seems like the film industry should have been thinking about it too, at least a little. If the industry hasn’t already been using some form of OBSD (even if limited) behind the scenes before exporting specific mixes, particularly for all-CGI or heavily-CGI movies, that’s a shame. I would imagine that the shift would be welcomed by the people who do audio work, so long as the technology performs as intended.

William Henley

I am kind of with EM on this one. I can’t say I am a mixing professional, but have mixed a few things over the years for personal use. I have always thought it annoying that I had to position an sound in the soundfield by “Panning” the audio, and even more annoyed at having to create different sound mixes for the number of speakers. I have long wanted the ability to place an object in a field, maybe with some GUI that has a speaker diagram, and have it process the audio for me. I have felt this way for about 15 years, and I am actually shocked to hear that they are just now developing this. Either the industry is made up of way too many people who cannot embrace change, or the industry has issues foreseeing obvious progressions.

Not only is the idea of Atmos obvious, but I am shocked that it didn’t come out some 10 or 15 years ago. This just seems obvious for mixing sound in a surround enviornment.

Jonathan Doan

Great. A new reason to up the price of a movie ticket to $20 and beyond…