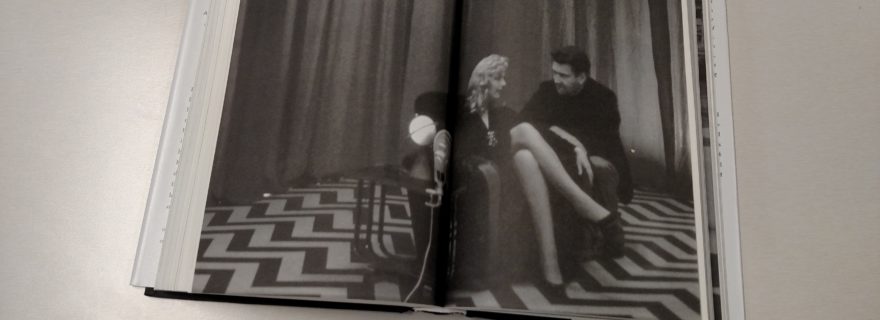

David Lynch has been such an idiosyncratic filmmaker throughout his four-decade career that it should come as no surprise his autobiography would also be a bit unconventional. Room to Dream provides perhaps the most detailed look at the man behind Blue Velvet and Twin Peaks that Lynch himself is ever likely to endorse, but unfortunately contains few revelations that longtime fans don’t already know.

Co-written with journalist and author Kristine McKenna, the hefty 592-page tome is part authorized biography and part autobiography. The book is organized in a mostly logical fashion, starting with Lynch’s early life and then progressing film-by-film through his career, from Eraserhead to Twin Peaks: The Return. (The sections on Mulholland Drive and The Straight Story are transposed for some reason.) However, chapters in each part alternate from a third-person biography written by McKenna to an autobiography transcribed from interviews with Lynch. In one chapter, McKenna will research the details of Lynch’s life and interview many of his friends, family, collaborators, and ex-wives. In the next, the filmmaker will react to what McKenna has written, filling in gaps she missed, explaining how he felt during that period, and sometimes contradicting the stories others told about him. This back-and-forth structure sometimes leads to repetition of stories, but also often forces readers to question the reliability of memory and just how much objective truth any biography can actually provide. On a number of occasions, I was reminded of the famous quote from Lynch’s Lost Highway: “I like to remember things my own way… how I remembered them, not necessarily the way they happened.”

The early chapters that cover Lynch’s childhood, his introduction to what he likes to call “the art life,” and his time studying at the American Film Institute are the most interesting. In these sections, we learn a lot about Lynch’s personal life and the events that formed him into the man and artist he would become. This part of his life culminates with production of his first feature, Eraserhead, which would establish him as a film artist with a decidedly unique cinematic voice. Eraserhead is the only of Lynch’s movies where the book delves deeply into the details of its production, describing its grueling journey from an idea in Lynch’s head to its unexpected success on the Midnight Movies circuit. These stories are fascinating, but have also been well documented before, from the special features on the Eraserhead DVD and Blu-ray to the 1997 Lynch on Lynch interview book by Chris Rodley.

In fact, anyone who’s read Lynch on Lynch will find the majority of content in Room to Dream familiar, if not redundant. Although the new book may flesh them out a little more thoroughly, Lynch has certain key stories that he likes to recount from each period of his life, forming the mythology of David Lynch as an icon of cult cinema and fringe art. Disappointingly, McKenna largely follows where Lynch leads and doesn’t dig up too much new material that fans haven’t heard before.

Because this is an authorized biography, the book maintains an unsurprisingly positive and supportive tone toward everything David Lynch has done, and tends to gloss over the darker periods in his life (except to note them as character-building) or any flaws in his behavior or personality. The chapters on Dune, which consumed more than four years of his life and ended in both critical and commercial failure, are disappointingly thin. Lynch claims he doesn’t want to dwell on those negative thoughts, but that experience forged him into the uncompromising filmmaker he later became. This is mentioned, of course, but lacks many specifics of what went wrong on that production. Likewise, Lynch shrugs off the poor reception Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me received, as if he always knew people would come around on it eventually.

As the book wears on, it reads less like a biography than a catalog of the many projects (film, painting, sculpture, and especially his promotion of Transcendental Meditation) Lynch has been involved in. In the later chapters, his personal life is mentioned less and less, and in increasingly superficial terms. Lynch has been married four times and had one child with each wife. Reading between the lines, he seems to be a pretty terrible husband and negligent father, but McKenna basically excuses this as a side effect of being such a dedicated artist, as if he simply doesn’t have time to waste on maintaining personal relationships. She acknowledges that he’s prone to infidelity and then she quickly moves on, never allowing his spurned partners a chance to share their feelings about his treatment of them. In particular, Lynch comes across as kind of a creep in the way he wooed the young intern who would become his fourth wife while still living with longtime girlfriend and collaborator Mary Sweeney (whom he would marry and quickly divorce shortly afterward). The fact that the fourth marriage would also eventually deteriorate is offered as almost an afterthought, as if it should be a given that he couldn’t make it work this time either.

Lynch’s oldest daughter, Jennifer, is interviewed to talk briefly about growing up on the set of Eraserhead, but McKenna fails to ever mention that she followed her father’s footsteps into filmmaking and (after a rocky start) has become a fairly successful TV director. That seems like it ought to be notable.

The last few chapters of the book are kind of a slog to read. Following the success of Mulholland Drive, David Lynch experienced a rather serious artistic decline that resulted in a lot of abjectly terrible video shorts shot in his backyard and the disastrous Inland Empire feature. At this point, McKenna’s respectful admiration devolves into fawning adulation, and she treats even nonsense like Crazy Clown Time (warning: NSFW) as if it were on equal artistic footing with Blue Velvet. She also seems to buy fully and uncritically into his devotion to Transcendental Meditation. The book then ends, naturally enough, with Lynch’s return to Twin Peaks, which is presented as a stunning success beloved by everyone, disregarding its ratings failure and the highly mixed reaction even among the show’s former fans.

Despite these issues, Room to Dream is mostly an enjoyable read filled with enough interesting tidbits to hold the attention of even those like myself who’ve heard most of these stories before. Somewhat surprising to me were the facts that: 1) Lynch holds almost the entire second season of Twin Peaks in great disdain, and 2) He initially did not want to complete Mulholland Drive as a feature film after ABC dropped it as a TV pilot, and probably wouldn’t have if one of the producers hadn’t threatened to sue him.

Rating: